17th June 2019

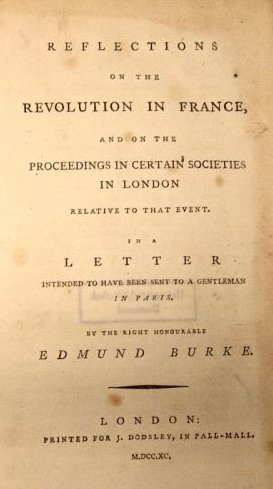

(Title page from the Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France, 1790)

*

Constitutional law should be boring.

For ages, the subject was boring – entire pages, sometimes entire chapters, of UK constitutional law books would have no leading cases from the lifetimes of those teaching the subject, let alone those being taught.

The party battles and the political crises would come and go, but the settled practices of the constitution would carry on much the same.

And now it is the most interesting time to be a constitutional lawyer in England since the 1680s.

(That last sentence is deliberately limited to England, as the constitutional histories elsewhere in the United Kingdom are different.)

This is not to say we have (yet) a constitutional crisis.

So far, our constitution has been (fairly) resilient in the face of executive power-grabs and novel predicaments.

The executive was stopped by the courts from making the Article 50 notification without parliamentary approval.

And the executive was then stopped by parliament (using at times some ingenious and arcane procedures) from taking the UK out of the EU without a deal.

Of course, neither of these outcomes were inevitable and could have gone the other way – and the latter may still happen on Hallowe’en.

But to the extent a constitution exists to resolve tensions so that they do not become contradictions, the UK constitution has done (generally) well so far with Brexit.

*

Over at Prospect magazine I have done a short piece on the constitution.

My argument in essence is that the test for a codified (or any) constitution is that it can recognise and regulate tensions between the elements of the state (the main elements being the executive, the legislature and the judiciary).

Some who read perhaps too quickly (if at all) raced to characterise my piece as an argument for an uncodified constitution.

But I am ultimately neutral on the form of any constitution – I am more interested in how well it functions.

Neither a codified nor an uncodified constitution is inherently superior.

The test is a practical one.

And the test for those who urge codified constitutions (who Edmund Burke wonderfully called “constitution-mongers”) is to show how their models and proposals would work.

It is not enough to assert that, of course, a codified constitution would be better as a matter of principle or of faith.

Show us the proposed constitutional code – the detail and the drafting – and let it be examined and tested.

**

Thank you for reading me on this new(ish) blog, where I am hoping to blog almost daily now I am back from a break.

I expect to be blogging here more often, instead of spending time on Twitter.

Please subscribe, there is subscription box above (on an internet browser) or on a pulldown list (on mobile).

**

Comments are welcome but pre-moderated, and they will not be published if irksome.

I am glad that you recognise that “the constitutional histories elsewhere in the United Kingdom are different”. However, although you may intend to return to the differences, by leaving it at that you are reinforcing the “traditional Westminster view of the United Kingdom as a unitary state …………”. To discuss Brexit from a purely anglocentric perspective fails to recognise that the Brexit Dilemma cannot be resolved without recognising that “at the periphery, there is a different view, which sees the U.K. as a union of nations …….”. See the contribution by Professor Keating ‘Brexit and the Nations’ to ‘Britain Beyond Brexit’ (Kelly and Pearce). Although I speak from a Scottish (Unionist) perspective I cannot but think that such a metro-centric approach has resulted in a failure on the part of the Brexiteers to understand the Irish dimension and in appallingly arrogant statements referring to the “Irish tail wagging the dog” (Javid and Johnson).

“purely anglocentric perspective”

Some phrases write themselves, don’t they? I spend years carefully ensuring I am not anglocentric when writing about public law. I have written about Brexit from the perspective of Scotland, Ireland, Gibraltar, and the EU. You will not find another English commentator on Brexit who tries harder to not be anglocentric.

But, to no avail.

Somebody comes along and types “purely anglocentric perspective” any way, because they cannot stop themselves.

For what it is worth, my view is not “anglocentric” – “purely” or otherwise.

I’d go further and say you’ve spent years avoiding having any opinion on Brexit whatsoever, anglocentric or otherwise ;)

What is fascinating and alarming to watch in the U.S. (I am a Brit, naturalised in the U.S, living in France, and newly naturalised in France) is the break-down in the rule of law and perhaps, the Constitution. In America there was a slightly smug assumption that the U.S. Constitution is robust enough to withstand any challenges. It is now abundantly clear that the weak point is Congress, the people’s branch.

As long as the people elect a president who is at least marginally rational and law-abiding, and as long as the people elect representatives and senators who are also rational, the Constitution will hold up.

What we have now in the U.S. is a president out for his own interests rather than those of the country, and a Senate that will approve almost anything the president wants, and will consent to almost any nominee to the federal courts and the Supreme Court. This is gradually eliminating the checks and balances provided in the Constitution.

In the end, the most careful deliberations of the founding fathers are not proof against rogue individuals, who gradually erect their own guard-rails against oversight.

AKA, all the checks and balances in the world only work so long as you don’t have baddies or loonies in all three branches of government at the same time.

You have stated on more than one occasion that “Some say the UK has an unwritten constitution, though this is not strictly correct. The constitution is written down, just not in one place.” While this is no doubt the case from a legal perspective (I for one have not had enough of experts) I am not sure it is true in ordinary speech.

You could argue that the ordinary meaning of “written constitution” implies something tangible, venerable and majestic, preferably inscribed on vellum, to which the legislature, judiciary and executive are all clearly subordinate, and which can only be altered through a special and difficult process.

And you are welcome to argue so. Especially as it is always nice to type “vellum”.

He most interesting subject.

I’ve spent much of the last week arguing the “people are sovereign” narrative, which usually stalls when I push for a definition of “the people” in that context.

The Executive of the last three years has much to answer for.

I am not a lawyer but enjoy your Twitter posts and look forward to reading this blog. I wonder whether you agree with this thought on our relationship to Europe and the current Brexit debate: there are it seems to me two constitutional issues at play here, and the question of written/unwritten constitution might be different for each. The public might be more comfortable in our relationship with Europe if that process by which EU law is transposed into domestic legislation were codified, while the debate over Brexit, and other constitutional issues, is best managed in an uncodified environment? Codified, it is more transparent. Uncodified, perhaps more agile.

The United Kingdom’s lack of a codified constitution carried the advantage of emphasising parliamentary sovereignty. But it also relied on an electoral system that delivered an executive that could comfortably command a majority in the Commons and, since the introduction in 1975 of the use of referenda, Prime Ministers capable of ‘interpreting’ the results of those referenda in a way that accorded with constitutional convention. The system has broken down irretrievably. We are already in the early stages of a serious constitutional crisis which, without correction, will lead to the end of the Union and threatens our democratic system itself. The answer: a codified constitution, probably resulting in PR, an elected upper house and clear and permanent rules for the future use of referenda. In other words, a 21st century political system to replace the 18th century system that once served us well, but no longer.

I love the blog but I also follow you on Twitter. Two points. I think a new and written constitutional settlement is inevitable given the fact of the devolved regions and the new tensions over Brexit. I used to argue this point in Constitutional Law classes at UCL in 1999. Second, when you posted an image of Edmund Burke’s masterwork I thought you were making the point that the current Conservative Party is now not dominated by Burkeans but flaming radicals. I am a fan of Burke and I shudder to think what he would make of the current mess.

I enjoy your writing.

Please write a post on how the position of ‘Prime Minster’ technically didn’t exist for a long time.

Brexit has destroyed the British (né English) Constitution. It has introduced a contradiction into the very heart how the constitution operates. One cannot have parliamentary supremacy and popular supremacy. It is diesel fuel in a gas engine; vinegar in milk; a lit match in a gas line.

The Brexit referendum also showed a total lack of understanding of how plebiscitary operates. Look at the Swiss. They’ve had them forever and the system works not just because of history but two major principles undergird it. The pros and cons of a the matter to be voted on are presented to voters by the government prior to the election in a neutral fashion. (A recent case negated a referendum because the information provided was deemed by the Court to be inadequate.) Fundamental matters require not just a majority of the votes to pass, but majorities in a majority of the cantons. (This is similar to the Australian Constitutional amending formula which requires majorities in a majority of the states with a majority of the national population. )

The Brexit referendum was defective in both of the Swiss principles.

Not a majority of the nations of the UK; no neutral information. (£350 million for the NHS per week!!!!).

Devolution was a typically clever constitutional invention to deal with the need to move beyond a unitary state but with 85% of the population in England, a recognition of the impossibility of federalism. (Some have argued that NSW and Victoria in Australia and Ontario and Québec in Canada, federalism in both countries is unbalanced by the size of the two most populous states/provinces.) The West Lothian question is beside the point as English MPs have a secure majority and can do what they wish and is another example of the evil hand of Enoch Powell reaching beyond the grave.

I actually am not a “Constitution-monger,” and the other realms that use the Westminster model seem to have (without codification) understood it better than Westminster itself.

As a Swiss abroad, I get to vote in (con)federal referendums. We’ve had them from 1875, though things do get modified from time to time.

There are 26 Swiss cantons or ‘counties’; some are very populous, such as Zürich; some have very small populations, such as Appenzell. Some are liberal, some are conservative; some are (mostly) Catholic, some Protestant.

Before any referendum, I get a booklet in the post laying out the reasons for the referendum, the view of the executive and the view of the proposers. Such referendums are debated in parliament, and the votes in both chambers are described. So, we are pretty well informed about the topic, even those of us who live in Norn Iron. I can vote over the internet.

In any federal referendum, as you say, there has to be a majority of the popular vote, and a majority of the cantons. Unless both conditions are met, the status quo cannot be altered.

This means that all the cantons, the fundamental constituents of Switzerland, have an equal say; the large, rich and liberal cantons cannot dominate the smaller, poorer and conservative ones.

Also, it is the people of Switzerland who are sovereign (as the papers always remind us before a referendum): it is not the parliament, it is not the executive, it is the people.

I have argued elsewhere that if the UK must have referendums, a similar principle should apply. Thus, England, Wales, Scotland and N Ireland would be the constituents.

In the Brexit referendum, had it been held under ‘Swiss Rules’, the popular majority was for Leave. There was no majority in the constituents for Leave, thus the status quo ante would have continued. And we would not have spent the last three years in Brexit-related spasms and torment.

Would it spoil your characterisation of the Constitution to suggest that the “main elements of the state” should be four – the three you list plus the Citizens, considered to act both as individuals and in groups?

All four elements are currently being abused by a monstrous hybrid that has steadily been acquiring enormous unchecked power – the political party machine.

And while I’m about it, may I suggest removing from your list of “other elements”, the media. It no longer fits the nice idea of the “free press” as it consists of a few profit-seeking commercial enterprises controlled by extremely wealthy oligarchs.

My aunt, who moved to Canada in the 1970s, told me once that the Canadians had come bitterly to regret putting their constitution in one codified document. They had discovered the hard way that a document ‘set in stone’ is immediately inflexible and incapable of coping with radical change.

The Constitution was not codified, it was patriated with an amending clause, a charter of rights and freedoms; it was also consolidated (amendments put into the relevant articles of the document itself; the former BNA acts were renamed Canada Acts. The Westminster model was not codified at all.

I don’t know where your aunt got her ideas, but they are wrong.

I’m not a lawyer. I enjoy and find your blog and twitter comments always enjoyable and interesting. So I look forward to reading more comments here. I take the point you are making about the the onus being on the “Constitution Mongers”, among whom I would count myself, to make the case in favour. But I think that to ask us to show you a detailed draft, how it would work and so on, is asking too much; it should surely be a collaborative effort, including those who are sceptical and could help ensure it is robust. But they are not going to cooperate in such an endeavour unless they must. So I look for an argument that encourages them to think they must because there is a moral imperative to do so. The best I have come up with so far is the following:

It should be a fundamental right for every person to be governed according to a Constitution that they can read and understand, having achieved a reasonable level of education. Everyone has a right to know what are the duties and obligations of the state which governs them, and in turn to know and understand all their duties as responsible citizens.

I wonder if the test you set up for the ‘constitution mongers’ is quite right; or at least, if it is possible for any constitution to pass it.

The behaviour of written constitutions in practice is pretty unpredictable. For example, the Irish constitution contains ‘Directive Principles of Social Policy’ which are intended to be non-justiciable and the Irish courts have respected this non-justiciable character pretty rigidly. The Indian constitution contains ‘Directive Principles’ which were modelled on the Irish example but the courts there have used them as a point of departure for a very activist approach to judicial involvement in policymaking. I’m just not sure that there is any robust empirical test we can set up for how a written constitution would operate once enacted and interpreted by legal and political elites. Culture is hugely significant, and the UK has quite a distinct constitutional culture that makes it fairly sui generis.

Something more concrete that we could test, or at least reasonably hope to compare with other jurisdictions, is whether some new institution would improve the current UK constitutional mix (citizen assemblies seem to be all the rage, so perhaps something along that line). But that is the kind of institutional innovation that could more easily be piloted within statute anyway, so again probably not a good empirical argument for a written constitution.

Some good reasons for a written constitution – although they are not knock-down reasons, and I’m not an unqualified advocate for one in the UK context:

1. ideological: there is a democratic, educative value in fleshing out more of the constitutional principles operating in the UK.

2. clarity: similar to the first, constitutional conventions have the advantage of flexibility, but they are premised to some extent on common understandings that really were common when most of the elite came from very similar privileged backgrounds. What was ‘the done thing’ was a robust and tangible standard. Now, in circumstances where politics is very fractured and significantly more ideological, key elite figures seem to misunderstand or misinterpret them.

3. cultural change: the move to a written constitution might create a cultural change along the same lines as was achieved with the Human Rights Act and the devolution settlements – the use of constitutional change to achieve a sea change in the way a particular issue was dealt with. Adoption of a written constitution might signal a break with democratic politics that have become defective.

But none of these are empirical arguments, and none of them are knock down arguments for a US-style constitution. (Actually I don’t think anyone should adopt a US-style constitution). A written constitution is a leap of faith.

But note that none of this requires a single, written, legally superior constitution. Adopting one is not an

I’m not a lawyer (or British), but most important difference between UK and countries with “written” constitution is the way it is changed or protected. Usually there are some higher requirements to change any constitutional amendment, like 2/3 of the vote in parliament. Without these protections, in UK, I see no legal protections from tyranny of majority. I know this goes against principle of “not binding” next Parliament, but even that principle is at the mercy of HoC majority. As you noted, whether it is written in one place (or not at all) is not really important. But this looks crucial difference to me, and was noted in one EU report on NI and Brexit recently as an argument to keep ECJ involved.