5 March 2021

*

‘Time to form a square around the Prittster’

– prime minister Boris Johnson, as reported on 20th November 2020

*

‘Expected value is the product of variable such as a risk multiplied by its probability of occurrence’

– Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation (‘the Green Book’), 2020 edition, p. 140

*

We now know what appears to be the financial value of a square formed about the Prittster.

According to my Financial Times colleague, the well-connected Sebastian Payne, the cost of yesterday’s settlement of the claim brought by Philip Rutnam against the home offic is at least £340,000 plus £30,000 of legal costs.

https://twitter.com/SebastianEPayne/status/1367517429115609091

There would also be other costs incurred by the home office, including for its own external counsel.

This is a substantial – indeed extraordinary – amount of money for a settlement of a claim – especially when on other matters the home office are often somewhat parsimonious over similar amounts of money

*

So what can be worked out about this settlement?

Let us start on a light note with how the news of the settlement was released.

Here we should imagine a zoom call discussion between a home office lawyer and media advisor:

Media adviser – How do we spin – I mean present – the settlement with Rutnam?

Lawyer – We can say we have settled without admitting liability

Media adviser – Doesn’t that just mean the same thing as the case has settled?

Lawyer – Yes, but political reporters will not know that

Media adviser – Ok – but can we pad it out even more?

Lawyer – We can also say that we were right to defend the case

Media adviser – But isn’t that just another way of saying no liability is admitted?

Lawyer – Yes

Media adviser – So we should say in effect that we have settled because we settled because we settled?

Lawyer – Exactly

Media adviser – And that will fill up their ‘breaking news’ tweets leaving little room for anything else – oh, that is genius

Lawyer – Thank you, that is kind

Govt and Sir Philip Rutnam have settled their case, after his explosive resignation last year – Home Office says "The Government does not accept liability in this matter and it was right that the Government defended the case.”

— Laura Kuenssberg (@bbclaurak) March 4, 2021

Ahem.

All that government statement says in that statement is that the home office has settled the case, three times.

*

More important – and interesting – is how that settlement amount was authorised.

The home office released this statement yesterday:

‘The government and Sir Philip’s representatives have jointly concluded that it is in both parties’ best interests to reach a settlement at this stage rather than continuing to prepare for an employment tribunal.’

This statement shows that a decision was made by the government to settle rather than to proceed to trial.

The statement also expressly states that this decision was made in the government’s best interests.

This indicates – if not demonstrates – that the decision to settle was made in accordance with the principles set out in the ‘Green Book’ – the common name for Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation.

The Green Book sets out how a government department should approach dealing with liabilities and risks.

In essence, the Green Book provides the basis for how cost-benefit analyses are conducted in Whitehall.

In civil service speak: ‘[e]xpected value is the product of variable such as a risk multiplied by its probability of occurrence’.

The ‘concluded…best interests’ language of the home office statement means that a decision was made that settlement was more beneficial to the home office than the risks of proceeding with the case.

Or more bluntly: the home office realised it was likely to lose at trial and to lose badly.

Only if this decision was made on that basis, would – absent a ministerial direction overruling officials – such a payment be permissible in accordance with Green Book principles.

And the ‘concluded…best interests’ language tells against any ministerial direction (which, in any case, would one day be disclosed).

So, if this assumption is correct, then the case was closed down not (just) to save a minister from embarrassment but because of the real risk of a heavy defeat at the tribunal – a defeat which ran the serious risk of costing the home office more than £370,000.

The prime minister may have wanted a square to be formed around the Prittster – but that would not itself explain a payment made in accordance with Green Book principles.

*

And so we come to the claim.

The amounts recoverable from most employment tribunal claims are capped, and so an employment tribunal claim even by a highly paid senior civil servant would not normally result in compensation in the area of the amount paid in this settlement.

And employment tribunals do not normally award costs – in lawyer speak, costs do not ‘follow the event’.

So what was different here?

If we go back to the statement made by Rutnam’s trade union when the claim was launched, there is a clue:

‘This morning, Sir Philip, with the support of his legal team and the FDA, submitted a claim to the employment tribunal for unfair (constructive) dismissal and whistleblowing against the Home Secretary.’

This was, in part, a whistleblowing claim.

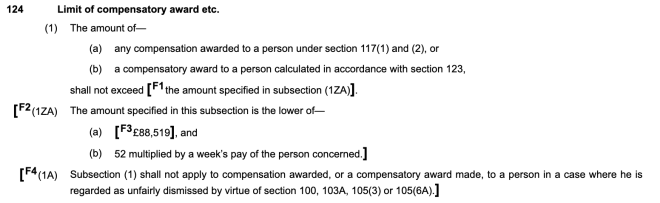

And as such – under sections 103A and 124(1A) of the Employment Rights Act 1996 (as amended) there is no cap on compensation if the reason – or principal reason – for the dismissal is in respect of a protected disclosure.

On this basis, and given the settlement amount, the claims made were regarded (at least potentially) as principally a whistleblowing case.

*

But – is not this case more about bullying than whistleblowing?

Here a passage in this Guardian report may be relevant:

‘Rutnam’s case was expected to focus on his claims that in late 2019 and early 2020 he challenged Patel’s alleged mistreatment of senior civil servants in the Home Office, and that he was then hounded out of his job through anonymous briefings.

‘Reports claimed that a senior Home Office official collapsed after a fractious meeting with Patel. She was also accused of successfully asking for another senior official in the department to be moved from their job.

‘Rutnam, a public servant for 30 years, subsequently wrote to all senior civil servants in the department highlighting the dangers of workplace stress. He also made clear that they could not be expected to do unrealistic work outside office hours.’

Under section 1 of the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 there are many ways a disclosure can qualify for legal protection – but the key thing is that such disclosure can be internal to a workplace, even to a boss, and not external disclosure to, say, the press.

On the face of the available information, and on the assumptions made above, it would appear that:

(a) in 2019-20 Rutnam made one or more disclosures internally within government in respect of workplace bullying;

(b) his claim for unfair dismissal in April 2020 had as a principal ground that such disclosure was the main reason for his constructive dismissal; and

(c) by March 2021 it was plain to the home office that this principal ground would be likely to succeed at trial.

Unless these (or similar) facts are true, then it is hard to explain why the home office, following Green Book principles, would settle this claim, for this amount, and at this time.

*

And so now: timing.

The obligations under the Green Book are constant and so would have been just as applicable when the claim was made as they are now.

But the home office waited nearly a year before settling the claim.

And a trial was fixed for September this year.

So something must have happened for the claim to have settled now rather than before now or later.

Something must have tipped the Green Book decision-making in favour of settlement.

There is more than one possibility for this.

It may well be that this was just when the settlement negotiations happened to come to an end, and the Green Book decision happened some time ago.

Or, if you are a conspiracy theorist, you can posit political pressure and even intervention – even though there is no evidence of a ministerial direction.

Or it could have something to do with the judicial review just launched by the FDA trade union in respect of bullying and the ministerial code.

But the most likely explanation is that something has happened in the litigation process that has changed things.

In civil litigation such a shift can sometimes be explained by some sort of costs tactic – where one side springs an offer with such costs implications which, in the words of the noted jurist Don Vito Corleone, is an offer that the other side can’t refuse.

But such costs traps are (I understand) uncommon in employment tribunal cases where there is a special costs regime.

*

So if not costs, then evidence.

At this stage of this sort of claim, there would be what is called a ‘disclosure’ exercise where the parties ascertain and share the relevant documentary and witness evidence.

It is the one moment when the parties get to see the actual strengths and weaknesses of their cases.

Other than in respect of costs traps, it is the one stage where claims are most likely to suddenly settle.

On this basis, the most plausible explanation for a claim that launched in April 2020 and was scheduled to be heard in September 2021 to settle in March 2021 is that some documentary or witness evidence has emerged – or has failed to come up to proof.

And given the nature of the claim and the amount at which the parties have settled, this development in respect of documentary or witness evidence would have to be in respect of a protected disclosure under the Public Interest Disclosure Act.

*

So if this is a whistleblowing case, does that mean the settlement silences the whistle?

Here one answer is given by section 43J(1) of the Employment Rights Act 1996:

‘Any provision in an agreement to which this section applies is void in so far as it purports to preclude the worker from making a protected disclosure.’

A similar answer is given by the Cabinet Office Guidance on Settlement Agreements, Special Severance Payments on Termination of Employment and Confidentiality Clauses:

‘Staff who disclose information about matters such as wrongdoing or poor practice in their current or former workplace are protected under PIDA, subject to set conditions, which are given in the Employment Rights Act 1996. This means that confidentiality 4 Settlement Agreements – guidance for the Civil Service – 18-July- 2019 clauses cannot and should not prevent the proper disclosure of matters in the public interest.’

On this basis, it is unlikely that the settlement agreement will contain such a confidentiality clause or, if it purports to do so, whether it would be enforceable.

The whistle is not silenced – at least at law.

It may well be that Rutnam believes his internal disclosures were sufficient.

Or it may well be that there may be another appropriate opportunity for disclosure, perhaps related to the FDA judicial review case.

We do not know.

*

But what we do know that the government has gone from this (as reported in the Guardian):

‘After a report in the Times highlighted tensions between Rutnam and Patel, sources close to Patel were quoted in several newspapers as saying that Rutnam should resign.

‘In an article in the Times, allies of the home secretary said he should be stripped of his pension, another source in the Telegraph said he was nicknamed Dr No for negative ideas, while one in the Sun likened him to Eeyore, the pessimistic donkey from Winnie the Pooh.

‘At that time the prime minister’s official spokesman said Johnson had full confidence in the home secretary and in the civil service, though the same guarantee was not given to Rutnam specifically.’

To this, in yesterday’s statement:

‘Joining the civil service in 1987, Sir Philip is a distinguished public servant. During this period he held some of the most senior positions in the civil service including as Permanent Secretary of the Department for Transport and the Home Office. The then Cabinet Secretary wrote to Sir Philip when he resigned. This letter recognises his devoted public service and excellent contribution; the commitment and dedication with which he approached his senior leadership roles; and the way in which his conduct upheld the values inherent in public service.’

And:

‘The government regrets the circumstances surrounding Sir Philip’s resignation.’

We can bet they do.

*

So, on the basis of the above we can perhaps understand how and why the government has settled at such a high payment.

The amount is not only ‘substantial’ – it is extraordinary.

And it can be explained best by an understanding of the Green Book as applied to the effects of relevant employment and whistle-blowing law in this particular case.

But what is perhaps most notable in yesterday’s statement from the government is what it does not say.

In his resignation statement, Rutnam said:

‘In the last 10 days, I have been the target of a vicious and orchestrated briefing campaign.

‘It has been alleged that I have briefed the media against the home secretary.

‘This – along with many other claims – is completely false.

‘The home secretary categorically denied any involvement in this campaign to the Cabinet Office.

‘I regret I do not believe her.’

As well as several other serious accusations against the home secretary.

Not one of these accusations is withdrawn – not even ‘clarified’.

The home office instead now commends ‘his devoted public service and excellent contribution; the commitment and dedication with which he approached his senior leadership roles; and the way in which his conduct upheld the values inherent in public service’.

If any square has formed, it is now around Rutnam and not the Prittster.

*****

Thank you for reading this post.

Each post on this blog takes time, effort, and opportunity cost.

If you value this free-to-read post, and the independent legal and policy commentary this blog provides for both you and others – please do support through the Paypal box above, or become a Patreon subscriber.

*****

You can also subscribe for each post to be sent by email at the subscription box above (on an internet browser) or on a pulldown list (on mobile).

*****

Comments Policy

This blog enjoys a high standard of comments, many of which are better and more interesting than the posts.

Comments are welcome, but they are pre-moderated.

Comments will not be published if irksome.

Note the word ‘guarantee’.

Note the word ‘guarantee’.