30th December 2020

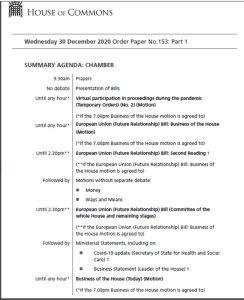

Today Parliament will be expected to pass, in one single day, the legislation implementing the Trade and Cooperation Agreement into domestic law.

This situation is exceptional and unsatisfactory.

The bill is currently only available in draft form, on the government’s own website.

As you can see, this means that ‘DRAFT’ is inscribed on each page with large unfriendly letters.

And we are having to use this version, as (at the time of writing) the European Union (Future Relationship) Bill is not even available parliament’s ‘Bills before Parliament’ site.

The draft bill is complex and deals with several specific technical issues, such as criminal records, security, non-food product safety, tax and haulage, as well as general implementation provisions.

Each of these specific technical issues would warrant a bill, taking months to go through the normal parliamentary process.

But instead they will be whizzed and banged through in a single day, with no real scrutiny, as the attention of parliamentarians will (understandably) be focused on the general implementation provisions, which are in Part 3 of the draft bill.

And part 3 needs this attention, as it contains some remarkable provisions.

*

Clause 29 of the draft bill provides for a broad deeming provision.

(Note a ‘clause’ becomes a ‘section’ when a ‘Bill’ becomes enacted as an ‘Act’.)

The intended effect of this clause is that all the laws of the United Kingdom are to be read in accordance with, or modified to give effect to, the Trade and Cooperation Agreement.

And not just statutes – the definition of ‘domestic law’ covers all law – private law (for example, contracts and torts) as well as public law (for example, legislation on tax or criminal offences).

It is an ingenious provision – a wave of a legal wand to recast all domestic law in whatever form in accordance with the agreement.

But it also an extremely uncertain provision: its consequences on each and every provision of the laws of England and Wales, of Northern Ireland, of Scotland, and on those provisions that cover the whole of the United Kingdom, cannot be known.

And it takes all those legal consequences out of the hands of parliament.

This clause means that whatever is agreed directly between government ministers and Brussels modifies all domestic law automatically, without any parliamentary involvement.

*

And then we come to clause 31.

This provision will empower ministers (or the devolved authorities, where applicable) to make regulations with the same effect as if those regulations were themselves acts of parliament.

In other words: they can amend laws and repeal (or abolish) laws, with only nominal parliamentary involvement.

There are some exceptions (under clause 31(4)), but even with those exceptions, this is an extraordinarily wide power for the executive to legislate at will.

These clauses are called ‘Henry VIII’ clauses and they are as notorious among lawyers as that king is notorious in history.

Again, this means that parliament (and presumably the devolved assemblies, where applicable) will be bypassed, and what is agreed between Whitehall and Brussels will be imposed without any further parliamentary scrutiny.

*

There is more.

Buried in paragraph 14(2) of schedule 5 of the draft bill (the legislative equivalent of being positioned in the bottom of a locked filing cabinet stuck in a disused lavatory with a sign on the door saying ‘Beware of the Leopard’) is a provision that means that ministers do not even have to go through the motions of putting regulations through parliament first.

Parliament would then get to vote on the provisions afterwards.

This is similar to the regulations which the government has been routinely using during the pandemic where often there has actually been no genuine urgency, but the government has found it convenient to legislate by decree anyway.

Perhaps there is a case that with the 1st January 2021 deadline approaching for the end of the Brexit transition period, this urgent power to legislate by decree is necessary.

But before such a broad statutory power is granted to the government there should be anxious scrutiny of the legislature.

Not rushed through in a single parliamentary day.

*

There are many more aspects of this draft bill which need careful examination before passing into law.

And, of course, this draft bill in turn implements a 1400-page agreement – and this is the only real chance that parliament will get to scrutinise that agreement before it takes effect.

You would not know from this draft bill that the supporters of Brexit campaigned on the basis of the United Kingdom parliament ‘taking back control’.

Nothing in this bill shows that the Westminster parliament has ‘taken back control’ from Brussels.

This draft bill instead shows that Whitehall – that is, ministers and their departments – has taken control of imposing on the United Kingdom what it agrees with Brussels.

And presumably that was not what Brexit was supposed to be about.

*****

This law and policy blog provides a daily post commenting on and contextualising topical law and policy matters – each post is published at about 9.30am UK time.

Each post takes time, effort, and opportunity cost.

If you value the free-to-read and independent legal and policy commentary both at this blog and at my Twitter account please do support through the Paypal box above.

Or become a Patreon subscriber.

You can also subscribe to this blog at the subscription box above (on an internet browser) or on a pulldown list (on mobile).

*****

This blog enjoys a high standard of comments, many of which are better and more interesting than the posts.

Comments are welcome, but they are pre-moderated.

Comments will not be published if irksome.